Author: Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Transportation is a service generating a substantial amount of information, and the diffusion of information technologies has transformed the mobility of passengers and freight.

1. Information Technologies and the Material Economy

Information and telecommunication technologies (ICT) diffusion resulted in several economic and social impacts. Historically, information required physical means to be diffused, implying that transportation and information diffusion domains were similar. For instance, postal services require physical means, making information mobility similar to freight mobility. The invention of the telegraph was the first significant technology contributing to the separation between transportation and telecommunications. Later on, the telephone, radio, and television would further contribute to this division by creating information networks separated from transportation networks. A new range of ICT that emerged in the 1980s contributed to reversing this trend by making telecommunication and transportation more integrated. These include computers, satellite communication, mobile phones, and the Internet.

Transportation is a service that requires and processes a large amount of information. The transport sector was conventionally perceived in terms of vehicles and infrastructure managed as assets delivering value by the mobility they confer to passengers and freight. For instance, transportation users decide where and when to travel, which mode to use if they operate their vehicle, and which routes to take. Inversely, the providers of transportation services must manage their assets to effectively match the demand (information) sent by various transportation markets in which they compete. Yet, the interactions between transport supply and demand are far from efficient, leading to enduring mismatches (overcapacity, under-capacity, and imperfect competition). Better sources of information and the ability to distribute information enable transportation systems to function with a higher level of efficiency because of better interaction between their supply and demand.

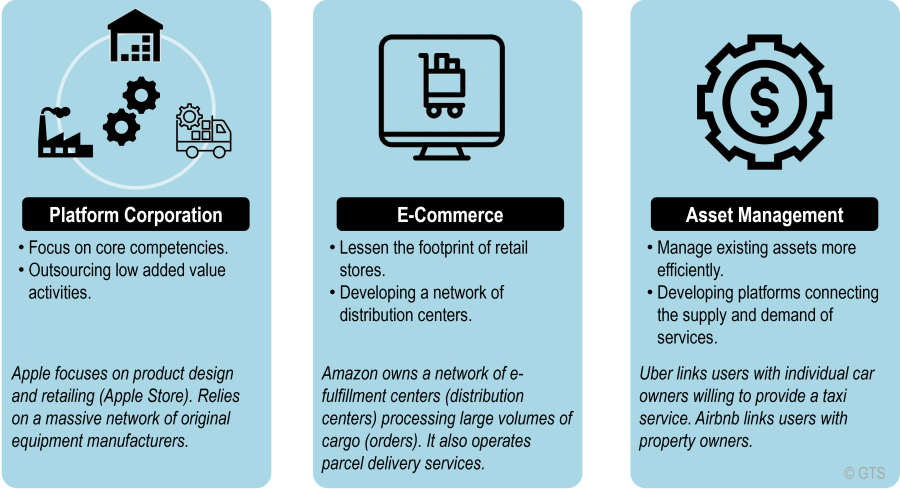

Looking at the potential impacts of ICT, such as the Internet, on mobility must consider how they can support, modify, expand, or substitute the mobility of passengers and freight. It is important to underline that information technologies do not lead to a dematerialization of the economy, which is a common misconception. This is associated with a series of paradigms:

- Platform corporation paradigm. Usually, a corporation focuses on core competencies (high-profit tasks) and outsources activities perceived as of lower value. In the manufacturing sector, it is common to focus on product design and retailing and rely on a network of providers to supply and assemble parts through outsourcing and offshoring. A platform corporation thus organizes the production, distribution, and retailing of the goods it sells. It indirectly and directly generates large amounts of material flows for the supply chains it manages through its information network. Still, the corporation itself may not be manufacturing any material goods.

- E-commerce paradigm. Online retailers have challenged the conventional paradigm in the retailing sector by acting as an intermediary between suppliers and consumers. They operate a network of e-fulfillment centers (distribution centers), storing hundreds of thousands of items, processing large volumes of orders that are packaged and delivered by postal or parcel services. A whole array of online retailers depends on material flows, with the distribution center as the key component of this strategy.

- Asset management paradigm. Elements of what has been labeled as the ‘sharing economy’ are more effective means to manage existing assets, such as real estate or vehicles, by linking providers and consumers. Even if the managing platform can be perceived as immaterial, it involves tangible assets that are more intensively used.

The above paradigms underline that the global economy is getting better at producing and distributing goods as well as managing existing material assets by creating extended market opportunities. At times, efficiency can be confused with immateriality because of the digital interfaces between assets and their users, including transportation.

2. The Digitalization of Transportation

With the emergence of an information society, the transactional structures of the economy have changed drastically towards networked organizational forms of individuals, institutions, organizations, and corporations with more intensive interactions, many of which are associated with new forms of mobility. Mobility can be provided in three major forms:

- Modal-oriented. The direct ownership and operation of modes and terminals by corporations (owning a fleet) or individuals (owning a vehicle for exclusive use). Ownership guarantees access to mobility at any time. Digitalization involves more efficient internal use of the assets such as tracking and navigation. Still, the optimal use is bounded by the ownership setting.

- Operation-oriented. The direct lease and operation of modes and terminals by corporations and individuals. Leasing guarantees access to mobility for the terms of the lease, such as time and condition. Digitalization involves making assets available across a market, reconciling supply and demand.

- Demand-oriented. Accessing mobility based on expected demand (for corporations) and need (for individuals). Digitalization involves accessing the availability of transportation assets in real time to rent their use temporarily.

Physical foundations, including transportation infrastructure, energy supply systems, and a regulatory environment, support mobility. The digital foundation (or digitalization) of this mobility is becoming increasingly important as it creates new transportation markets.

The three major spheres of the digitalization of transportation involve:

- Personal. ICT enables individuals to interact through additional mediums (e.g. email, messaging, video conferencing), which may lead to more interactions, but also to changes in how these interactions are conducted. The diffusion of mobile personal computing devices (e.g. laptops, smartphones, and tablet computers) has also enabled individuals to enrich their mobility by performing various tasks in transit or outside a conventional work setting. Several applications, such as global positioning systems, also enable individuals to manage their mobility better. The intensity and the scheduling of mobility can become highly interactive since users are able to coordinate their mobility considering real-time changes, such as congestion or changes in time and cost preferences. The smartphone acts as a trip optimization device that has improved the efficiency of vehicles through less confusion and errors, as well as the capability to re-route because of changing traffic conditions. At the aggregate level, these improvements are substantial and could be associated with 10 to 20% in overall efficiency improvements.

- Consumer to business (C2B). ICT enables consumers to interact with the transportation services they use more effectively. A direct form is purchasing transport services, which are now online through air and rail transport and ride-sharing services booking systems. An indirect form is E-commerce, which has opened a whole new array of commercial opportunities complementing or substituting conventional shopping, from basic necessities to discretionary goods. One important convenience of e-commerce is removing the distance and temporal restrictions associated with conventional retailing. Customers needed to physically travel to a store, which had defined opening hours. E-commerce does not necessarily imply more consumption but that a growing share of retailing transactions is taking place online, resulting in the growth of home deliveries, which are an indirect form of transportation.

- Business to business (B2B). ICT enables businesses to transact more effectively, indirectly resulting in changes in their transport operations. The increasing scale and intensity of business transactions are commonly linked with supply chain management strategies. For instance, inventory management strategies permitted by ICT enable a more significant share of the inventory to be in transit (‘stored’ in vehicles and at terminals), often in line with an increase in the frequency of deliveries.

The digitalization of transportation incites the development of new platforms where actors can interact in providing, using, and exchanging transportation services. The conventional urban mobility landscape is characterized by a patchwork of passengers and freight transportation services, which is associated with the inefficiencies of these assets. By integrating transportation service providers in an ICT platform, a new paradigm emerges, which is referred to as mobility as a service.

Mobility as a service concerns transactions related to transportation and supply chains. Conventionally, each actor along a transport chain tended to keep its own centralized ledger recording its information and transactions. The emergence of Blockchain technologies provides an extended and distributed form of ledgers, adding value to the process. It can potentially improve the transactional efficiency of supply chains by enabling the providers and users of transport services to share a common and distributed electronic ledger system. Exact copies are maintained and simultaneously updated across several nodes. It becomes possible to more effectively manage access to transport infrastructures and conveyances (from a seat in a plane to a slot in a containership), the related data exchange, and payments for service provided.

3. Telecommuting and Tele-Consuming

One of the ongoing tenets is that ICT can offer forms of substitution for the physical mobility of passengers and freight. When this substitution involves work-related flows, it is called telecommuting, and when it involves consumption-related flows, it is called tele-consuming.

Telecommuting. Using information and telecommunication technologies to perform work at a location away from the traditional office location and environment. Commuting is thus substituted, and it is implied that it took place remotely instead.

Tele-consuming. Using information and telecommunication technologies to consume products and services that would typically require a physical flow to access.

Both have been facilitated by advances in information technologies, particularly the ubiquity of high bandwidth connectivity and mobile devices. There are degrees of telecommuting ranging from a partial substitution, where a worker may spend one or two days per week performing work at another location, to a complete substitution, where the work is performed elsewhere, such as in an offshore location. The latter is much less likely as the vast majority of work tasks tend to be collaborative and require face-to-face meetings.

Tele-consuming is more ambiguous and the main factor behind the perception of a dematerialized economy. For instance, many media such as books, newspapers, magazines, movies, and music used to be physically delivered and consumed; they are now mainly accessed (consumed) online. Software and operating systems that used to be distributed through physical means, such as on disks, can be downloaded directly. Still, telecommuting and tele-consuming require substantial telecommunication infrastructure and networks to be effective.

Telecommuting has often failed to meet expectations, and its share of total commuting movements remained low and relatively unchanged; 3 to 5% of the total workforce can telecommute at least once a month, but this share appears to be growing slightly. Many reasons exist for this enduring low share, ranging from activities that cannot be easily substituted to a loss of direct control from management because workers are not present on site. One major factor is that if a job has the potential to be complemented by telecommuting, it is also a target to be relocated to a low-cost location either through outsourcing or offshoring. Thus, a large amount of telecommuting took place as offshoring instead. Also, many workers use telecommuting forms to work overtime, carry extra work at home, or perform other activities that may still require transportation. Therefore, telecommuting allows employers to impose longer work hours and ensure employees are more available for work on an on-call basis outside regular working hours.

4. ICT and Location

In addition to substitution and mobility issues, ICT impacts the location and the operations of economic activities. The most important forces are decentralization and relocation. Organizational structures are being transformed from a hierarchy to a network of collaborators. This commonly results in management that is more flexible and able to adapt to market changes, including new sourcing strategies. ICT improves locational flexibility by offering a wider array of locational choices for administrative, retail, and freight-related activities. This helps lower office and retail footprints by decentralizing some tasks to a lower-cost environment, such as the suburbs or at home, or by permitting their complete relocation (offshoring) to low-cost locations. ICT is, therefore, a corporate strategy to improve the productivity of labor and assets through higher locational flexibility.

Central locations and larger building sizes have dominated retailing and offices since the 1950s. Indeed, newer and larger stores overtook smaller rivals and established new distribution structures based on mass retailing. The standard 2,000 square feet market of the 1950s became the 20,000 square feet supermarket in the 1960s and evolved into the 50,000 square feet superstore of the 1990s and the 200,000 square feet supercenter of the 2000s. The retail real estate footprint increased substantially during that period, particularly in North America. Following a similar trend, the small office of a company has become several floors in a skyscraper located in the central business district. The amount of space devoted to administrative functions has increased significantly.

While ICT initially allowed administrative functions to be more productive without much impacting the demand for office space, as ICT matured and became ubiquitous, its locational impacts became more apparent. ICT is changing retailing by rendering some location structures obsolete. The impacts of e-commerce are particularly salient since they permitted new forms of distribution and retailing. Since the distribution center is taking a core role in e-commerce, suburban locations are becoming the setting for new types of facilities such as e-fulfillment and sortation centers.

Most corporations use ICT to reduce costs. For office-related activities, the costs of providing office space to employees are far more than just the cost of leasing or owning. It also concerns parking, which tends to be more expensive in high-density areas. It can sometimes run as high as 20 to 30% of disbursed salaries per employee. With these high costs, a common outcome was outsourcing or offshoring the job instead of focusing on telecommuting. If a job could be substituted by telecommuting, it could be more cost-effective to outsource it instead. However, the growth of teleconferencing technologies has widened options. The wide availability of teleconferencing technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 allowed sectors such as education, civil service, and management to remain functional despite lockdowns. However, it was also realized that many jobs could remain offsite, leading to a substantial decline in the demand for office space once the pandemic ended.

In the retail sector, the most important cost is renting store space. This leads to the conventional paradox that the locations that could generate the highest sales volumes also commanded the highest rents. A factor behind the competitiveness of online retailing firms is their lower rent structure because their footprint is more focused on distribution centers in lower-cost locations. They are not burdened with maintaining a retail presence in high-cost locations.

ICT has thus become a force shaping land use and transportation. Cheaper space in the suburbs is an important requirement for newer and smaller firms that are users of telecommunications technologies. A similar observation can be made concerning the distributional structures related to e-commerce, in which fulfillment centers have suburban and exurban locations. The most recent trends in teleconferencing provided an additional dimension with capabilities to undertake educational, conferences, and office work remotely. The growing capability of ICT allows businesses and other organizations locational flexibility and better tracking, asset management, and regulatory compliance of transport systems.

Related Topics

- B.23 – The Digitalization of Mobility

- B.10 – Transportation and Blockchains

- 8.3 – Urban Mobility

- 8.4 – Urban Transport Challenges

- 2.2 – Transport and Spatial Organization

- 2.3 – Transport and Location

Bibliography

- Birtchnell, T. (2016) “The missing mobility: friction and freedom in the movement and digitization of cargo”, Applied Mobilities, Vol. 1, pp. 85-101.

- Cramer, J. and A.B. Krueger (2016) “Disruptive Change in the Taxi Business: The Case of Uber”, NBER Working Paper No. 22083.

- Gossling, S. (2018) “ICT and transport behavior: A conceptual review”, International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 12(3), pp. 153-164.

- International Transport Forum (2018) Blockchain and Beyond: Encoding 21st Century Transport, Paris: OECD.

- Janelle, D.G and A. Gillespie (2004) “Space-time constructs for linking information and communication technologies with issues in sustainable transportation”, Transport Reviews, 24, 665-677.

- Mokhtarian, P. L. (2009) “If Telecommunication is Such a Good Substitute for Travel, Why Does Congestion Continue to Get Worse?”, Transportation Letters, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1-17.

- Mulligan, C. (2014) ICT and the Future of Transport, Ericsson, Networked Society Lab.

- Schwanen, T. and M.P. Kwan (2008) “The internet, mobile phone and space-time constraints”, Geoforum, Vol. 39, pp. 1362-1377.

- Thomopoulos, N., M. Givoni and P. Rietveld (eds) (2015) ICT for Transport: Opportunities and Threats, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- US Department of Transportation (2015) 2015 OST-R Transportation Technology Scan: A Look Ahead, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center.

- Wang, Y. and J. Sarkis (2021) “Emerging digitalisation technologies in freight transport and logistics: Current trends and future directions” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 148.